When it was released in 1997, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure marked just one of the films that year starring lead actor Koji Yakusho. In addition, he starred in Shohei Imamura’s Palme d’Or-winning The Eel (also playing at this year’s TIFF) and Yoshimitsu Morita’s box-office hit Lost Paradise.

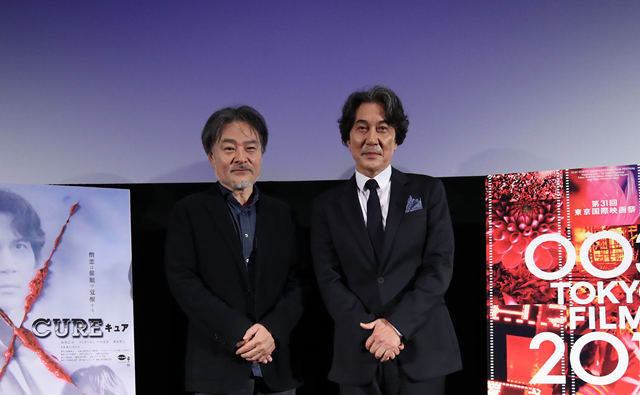

Kurosawa and Yakusho went on to collaborate on eight films, but Cure was their first venture together. The director and star fielded questions on October 27 following a screening of Cure in the Japan Now section, where the illustrious star is being honored as the Actor in Focus.

In the film, Yakusho plays police detective Takabe, who is investigating a series of murders with the same M.O.: two slashes across the throat and chest in the shape of an X. Strangely, all of the murderers are found and arrested within a short distance from the scene of the crime, though none appear to have any motive or reason for the murder. The only connection is that the killers came into contact with a morose young man in a long coat (Masato Hagiwara) who appears to have amnesia. As Takabe obsesses over finding answers to the case, while also taking care of a wife who is suffering from the early onset of dementia, it seems he may be losing his mind.

Unlike its contemporaries The Ring or The Grudge, which were leading the vanguard of J-Horror films, Cure’s scares came not from ghosts or cursed spirits, but from an eerie sense of dread that permeates the everyday. “To me,” remarked Yakusho, “it’s not a horror film. It’s a monster movie about a monstrosity of a man.”

Asked why he wanted to cast Yakusho in the lead role, Kurosawa explained that he felt the actor was ideal for the part and had drawing power as a star. When the actor accepted, it was to the director’s surprise and delight.

“But to be honest,” he confessed, “I just wanted to do a film with Koji Yakusho. He possesses the full range of human potential and expression; in any film, he could be a saint or a killer, and you can never easily get a read on him. I don’t think any actor then or now possesses such range.”

Ambiguity is the theme of the Japan Now section this year, and much of Cure’s ambiguity plays out in incredible long takes where the characters slowly reveal their madness. Kurosawa develops such scenes in medium shots where nothing of significance seems to be happening before the audience is jolted out of its rhythm. While the approach seems martinet, the director explained that he does not actually spend much time shooting or even rehearsing such elaborate scenes. “It’s probably from my background in V-Cinema, where we had to shoot films very cheaply,” he said. “Cure was shot on film, so we had to be even more judicious with time. But probably other directors work too much. I myself like working from 9-5.”

“Your crew probably loves you,” joked Yakusho.

Kurosawa deployed long takes for the film, and Yakusho’s versatility is showcased in scenes where he deftly expresses empathy, rage and anguish all in the span of a single shot. “To me,” he said, “to see such scenes play out without a cut is the unique power of cinema.”

Cure does not explain itself, and Yakusho often asked Kurosawa the meanings behind certain scenes. “But he never told me,” laughed Yakusho.

“I didn’t actually know myself!” replied Kurosawa. “We ended up discussing the screenplay several times at the Royal Host family restaurant near my house. I felt bad asking such a great actor to come to a place like that.”

Another ambiguity is in the title of the film, which was originally called The Missionary, but ended up being titled Cure by a producer at Daiei. The title evoked a religious or cult-like feeling that would have been timely, considering the poisonous gas attack in Tokyo subways carried out by the Aum Shinrikyo cult just two years earlier.

Screening over 20 years since its release, Cure has lost none of its unnerving power, and many in the audience wanted answers to the film’s still-puzzling elements. A two-second shot of a red dress, for example, was revealed to be a reference to a similar dress in Henri Georges-Clouzot’s Diabolique, foreshadowing the premonitions of Takabe’s wife’s death.

Both director and star provided commentary on the cryptic ending as well. “We actually shot more,” Kurosawa explained. “The waitress enters the kitchen and butchers her boss – but I felt that was too much and edited it to what we see in the film.

Asked about the significance of Takabe’s changed appetite in the two scenes in the diner toward the end of the film, Yakusho replied, “Takabe is a ball of stress from the investigation and from taking care of his wife. He has no appetite from this. But by the end of the film, all of his stress has disappeared. To me, the scariest thing is a man who feels no stress at all.”

Kurosawa agreed: “Yes, he is completely empty by the conclusion. Mr. Yakusho was able to depict this invincible state in the end.”

“It’s chilling to think that these kinds of truly scary people are among us,” concluded Yakusho.